Last October, K-pop singer Goo Hara took to Instagram and completely broke down. She was mourning the loss of fellow K-pop star Sulli, a former member of the wildly popular girl group f(x). Sulli had died by suicide, found the day before by her manager, no note left behind.

In her livestream, Hara’s tear-stained face was swollen with grief. She didn’t comment on the circumstances surrounding Sulli’s death—instead, for three minutes, she spoke as if she were saying goodbye to her best friend. Her “sister.” She apologized that she would have to miss the funeral because she was stuck out of the country for work.

Thousands of fans watched Hara’s pain unfold in real time. They left broken-heart emoji in the comments and asked if she was okay. “I will live twice more diligently,” Hara said. “Dear fans, I will be fine. Don’t worry about me.”

A little over a month later, Hara, too, would take her own life.

The thing about K-pop is that while other music might make you feel moody or mad at your ex or over it all, K-pop makes you feel good.

The sticky, upbeat songs never get unstuck from your brain, and you don’t want them to. Artists are both memes and icons, putting on the kinds of performances that require all caps to describe. Impressive for a class of music that’s new(ish): It really took off in 2012 around the time Psy’s hit “Gangnam Style” went viral. Today, it’s a multibillion-dollar business. Boy band BTS brings in $3.6 billion to South Korea’s economy every year all by themselves.

And that’s just at home. Across the world, stadium-size shows routinely sell out. When BTS added a last-minute stop in New York City to its 2019 tour, tickets were gone in less than 20 minutes. Stars regularly appear on morning shows, late-night TV, and red carpets proselytizing K-pop’s peppy, polished reputation. It’s what they’re asked and allowed to do.

What they’re not allowed to do is reveal the often toxic, manipulative, and inhumane circumstances behind the scenes that push some performers to extremes. “K-pop’s history is a history of cover-ups,” says John Lie, author of K-Pop: Popular Music, Cultural Amnesia, and Economic Innovation in South Korea. “Exploitation is one of the worst abuses.”

Exposing the industry’s insidious problems has been next to impossible, largely because the perpetrators are the singers’ own bosses. “What makes K-pop different—and more exploitative in some ways—is that artists are employees,” explains Lie. All-powerful entertainment companies dictate their every public (and sometimes private) move. In fact, stars are often bound by ironclad contracts that prevent them from speaking out.

I would know. I reached out to dozens of people in K-pop and I was continually ignored, ghosted, or strung along. This story almost didn’t happen. Until one artist finally agreed to speak to me.

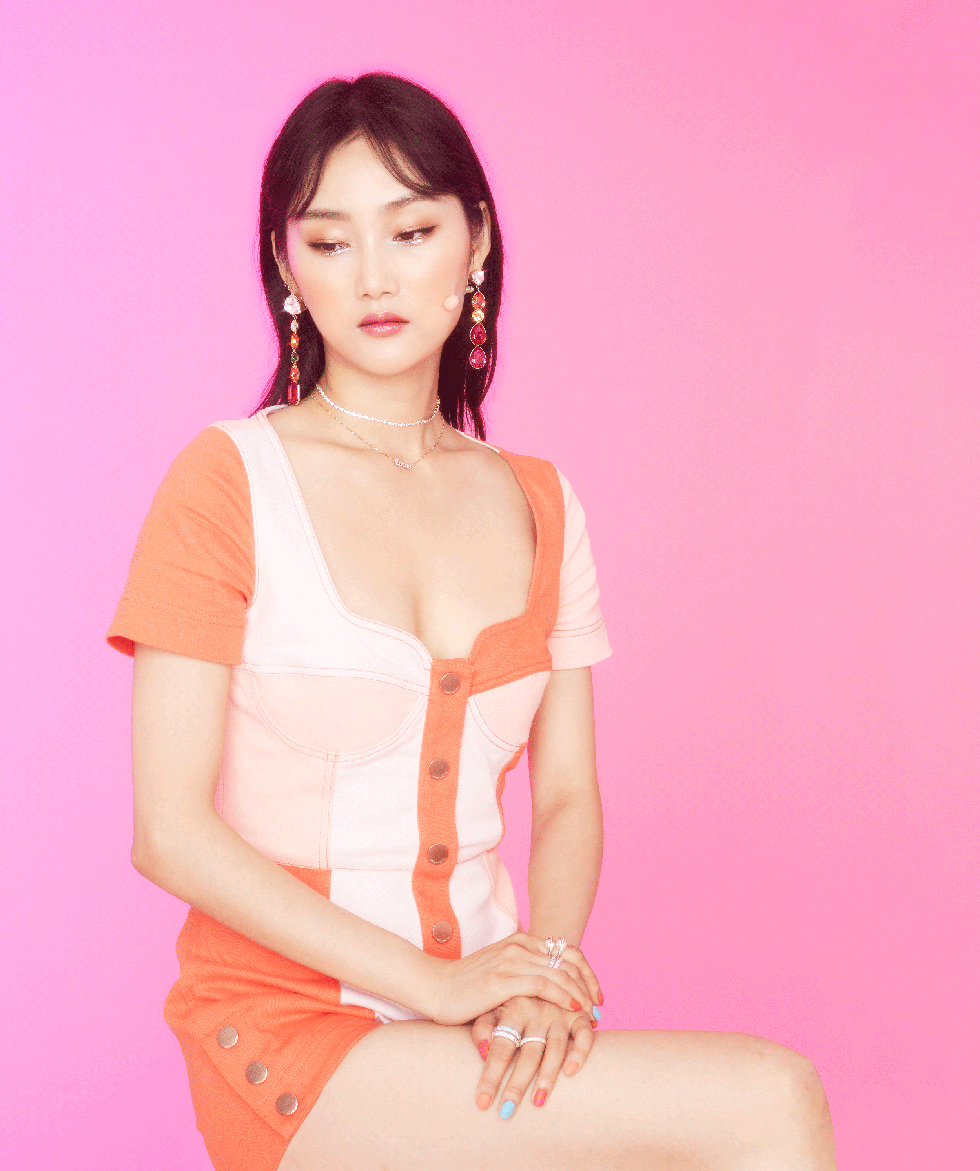

“Many artists don’t want to talk because they get threatened—they’re afraid of being blacklisted from the industry and feel powerless compared to the companies,” K-pop artist, songwriter, and YouTuber Grazy Grace exclusively tells Cosmo. “But it was important for me to speak honestly so that others don’t make the same mistakes I did.”

It all starts in the dorms. Unlike here, where getting a music executive’s attention can be a stroke of luck, there’s really only one funnel into the world of K-pop: participating in often years-long training programs run by entertainment companies whose goal is to mass-produce punch-cut pop stars like an assembly line, exporting the better-than-perfect ones onto the stage.

Trainees can start as young as 11 years old. Many cram into rooms (in Grace’s case, with eight other people), sleeping on bunk beds or the floor. Living away from family and friends, typically in Seoul, they’re forced to work 12-hour days or longer, memorizing lyrics and dance moves, practicing until they don’t make a mistake. All for free. “Payment” comes in the form of a room and dance and voice lessons…and sometimes nose jobs and double-eyelid lifts so aspiring stars can look the part.

“It was my dream to become a singer,” says Grace, who went through training in hopes of being chosen for a girl group. “Until I realized how bad it was mentally. I developed insomnia. I couldn’t sleep for six months straight. I started to feel anxiety but didn’t even know what an anxiety attack was. I didn’t want to share my feelings because I didn’t want to get cut from the company. I thought if I looked too depressed, I’d be let go.”

So she dealt with verbal attacks whenever her voice cracked. She kept quiet through weekly weight checks. Girls like Grace weren’t allowed to gain even one-quarter of one pound, she says. (In 2018, Momo, a singer in the K-pop group Twice, posted on the social media platform Vlive that she was only eating one ice cube a day until she dropped more than 15 pounds.)

“You kind of lose who you are,” says Grace. And that’s not by accident. Some trainees’ rooms are monitored by closed-circuit cameras, and cell phones are frequently checked by managers. Social media posts, too, must often be approved, every single selfie scrutinized before posting. (Part of this is to make sure there’s no interaction with a trainee of the opposite sex. Romantic relationships could result in termination—even actual K-pop Idols, as those who “make it” are called, are often contractually barred from dating for the first few years of their career in order to appear available.)

And once you’re in, you’re in. Some trainees sign contracts that stipulate that if they quit, they have to pay back everything the program invested in them. Depending on the company, that can be tens of thousands of dollars.

Most won’t though. Grace didn’t. After three years of strenuous, unpaid work, the company let her go.

For those fortunate enough to reach Idol status, things don’t get better. Sometimes, they get worse, for little more than the illusion of being rich and famous. Because while K-pop concerts sell out in minutes, some artists can’t even afford to buy a friend a last-row ticket to their own shows. When Lee Lang won Best Folk Song at the 2017 Korean Music Awards, she used her speech to auction off her trophy to pay rent. There was laughter and then an uncomfortable silence in the room—until someone piped up and bought it for $422.

“K-pop musicians don’t enjoy much wealth,” says Lie. Instead, their predatory contracts, which can outlast their careers, allow for very little compensation. That’s because most artists aren’t really viewed as artists at all but as assets.

While profiteering off pop stars is hardly a new thing (see: Lou Pearlman, the notoriously exploitative manager of the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC), it’s especially intense in K-pop. “Companies are trying to maximize profits in a short amount of time,” says K-pop expert Hye Jin Lee, PhD, a clinical assistant professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. “The career life span of an Idol is very short.” Few make it to 30.

For women, the problems compound. While female stars aren’t usually allowed to be in a relationship, that doesn’t stop managers from selling sexualized personas of them to fans. Once, a male investor even tried to broker a deal to take Grace to “dinner” for $30,000.

It never went through, and Grace only found out about it when a mentor told her more than a year later. “Maybe it happened all the time behind my back,” she says. Others in the industry have been pressured into prostitution—one CEO was sentenced to prison for his role in pimping out artists.

Add it all up—the greedy, grabby behavior of those at the top; the nonstop pressures; the steady abuses to body and soul—and it’s clear that the deaths of stars like Hara and Sulli aren’t just sad tragedies but dire warnings.

Many K-pop stars have reached rock bottom when it comes to their mental health, and they need help. Yet in an image-obsessed industry, in a country where talking about mental health is taboo, few are likely to get it.

Take Kim Jong-hyun, a singer in the popular K-pop boy band SHINee. In 2017, he took his own life, leaving behind a note suggesting that the pressures of the industry contributed to a depression he could not overcome.

About the future: Some would-be Idols are starting to forge their own career paths through social media, giving them the opportunity to step over abusive systems and put music out on their terms. “It’s easier to be independent now than it was before,” says Grace, who, over the past three years, has slowly built an audience of more than 200,000 subscribers on YouTube. “You see it more: people breaking out from their old companies and making it on their own.”

And while talking about mental health has long been considered off brand, more and more stars are starting to do it anyway. Like K-pop artist Taeyeon of Girls’ Generation, who opened up to fans on Instagram about how she’d been taking antidepressants, and BTS rappers Suga and RM, who regularly use their platforms to talk about issues like depression and anxiety.

“As more K-pop artists get vocal about their issues, the companies will start realizing that they need to do something,” says Lie. Adds Ju Oak Kim, PhD, assistant professor at Texas A&M International University: “Dramatic changes might not happen in a short period, but there will be changes.”

Here’s one: BTS was recently given time off for an extended vacation—for the first time in six years.

Model photographs by Ina Jang. Photos are of a professional model and used for illustrative purposes only.

Maria Sherman is a senior writer at Jezebel and the author of LARGER THAN LIFE: A History of Boy Bands from NKTOB to BTS. She lives in Brooklyn.

Photo credit: Jatnna Nuñez